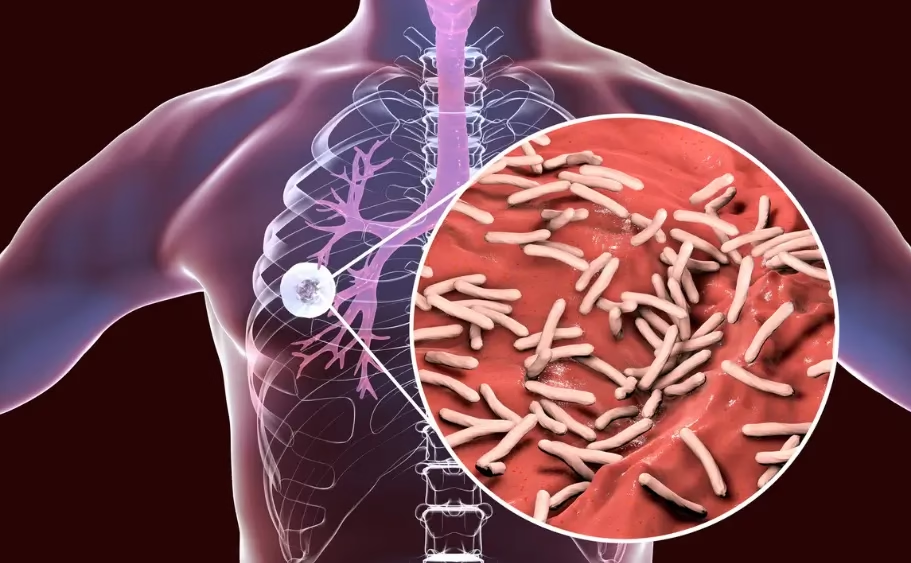

Tuberculosis (TB) has remained one of the world’s toughest diseases for more than a hundred years persistent, adaptable, and deadly. Caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis, it continues to resist medical advances. Despite vaccines, antibiotics, and global public health programmes, TB continues to strike millions every year.

In 2023, around 10.8 million people developed the disease and 1.25 million lost their lives. India shoulders the heaviest burden, reporting over 2.6 million cases in 2024. Put simply, TB remains firmly entrenched and scientists are still trying to understand how it manages to survive despite aggressive treatment efforts.

A big part of the puzzle lies in TB’s ability to shift into a dormant state. Inside the body, the bacteria can slow down dramatically a phase known as latent TB during which they stay alive but nearly inactive. There are no symptoms, no transmission, and often no warning. But if the immune system weakens due to illness, HIV, or certain medications, the bacteria can “wake up” and reactivate.

This dormant phase is where most antibiotics fail. Drugs designed to kill actively dividing bacteria barely affect slow-growing ones, allowing them to outlast treatment. This phenomenon is known as antibiotic tolerance.

A collaborative team led by Prof. Shobhna Kapoor (IIT Bombay) and Prof. Marie-Isabel Aguilar (Monash University) set out to understand why. Their findings published in Chemical Science reveal how TB bacteria protect themselves during dormancy, and why targeting this protection could make current drugs far more powerful.

Earlier clues suggested the secret might lie not inside the bacterium, but in its outer barrier a lipid-rich membrane that acts like a protective fort. Prof. Kapoor’s group examined how this membrane changes when TB shifts from an active to a dormant state, and whether those changes block antibiotics from entering.

Because handling live TB is risky, the researchers worked with Mycobacterium smegmatis, a safer relative that behaves similarly. They grew the bacteria in two conditions: one actively multiplying, the other mimicking TB’s dormant mode. The bacteria were then exposed to four well-known TB drugs rifabutin, moxifloxacin, amikacin, and clarithromycin.

The difference was stark. Dormant cells needed two to ten times higher drug concentrations for the same effect. Importantly, the bacteria had no genetic mutations linked to drug resistance. Something else likely the membrane was responsible.

Using advanced mass spectrometry, the team catalogued over 270 different membrane lipids. Actively growing cells were rich in glycerophospholipids and glycolipids. Dormant cells, in contrast, were coated with fatty acyls heavier, wax-like lipids that form a tougher defensive layer. “We found clear, consistent differences between active and dormant lipid profiles,” said lead author and PhD scholar Anjana Menon.

The physical changes were equally compelling. Fluorescence-based measurements showed that active bacterial membranes were fluid and loosely packed, while dormant membranes became rigid and tightly arranged almost armour-like. Levels of cardiolipin, a lipid that helps keep membranes flexible, dropped sharply in dormant cells, making the outer layer even more impenetrable.

Tracking rifabutin confirmed the impact: the drug easily permeated active cells but barely entered dormant ones. “The rigid membrane forms the bacterium’s most important protective barrier,” Prof. Kapoor explained.

If the shield is the issue, breaking it down could be the solution. Instead of inventing entirely new antibiotics, the researchers propose enhancing existing ones by pairing them with molecules that soften the membrane. One promising option is antimicrobial peptides small proteins that gently loosen lipid layers. These peptides don’t kill the bacteria on their own, but in combination with antibiotics, they help drugs penetrate more effectively.

The team’s next goal is to repeat this work using actual Mycobacterium tuberculosis in high-containment laboratories. “Our lipid mapping is extremely detailed and can be applied directly to studies with the real TB pathogen,” Ms. Menon noted.

If the approach succeeds, it could shorten TB treatment, make current drugs more effective, and offer a new strategy against a disease that has held its ground for over a century.